|

Philosophy from All Walks of Life

Michigan State University Kellogg Conference Center October 17-19, 2019 Call for Workshops, Panels, Papers, Reports Due January 31, 2019, please submit to: https://easychair.org/conferences/?conf=ppn2019 The Public Philosophy Networks invites proposals for its fifth conference, Philosophy from All Walks of Life, hosted by Michigan State University, October 17-19, 2019. Starting from the tradition of Detroit activist Grace Lee Boggs, the conference continues the PPN practice of expanding philosophy outside of the academy into everyday life, serving as a resource for social change. To this end the Public Philosophy Network invites proposals from philosophers, broadly construed, outside of and inside of the academy whose work seeks to utilize philosophy for socially relevant outcomes. Conference events include: An evening dedicated to the work of philosopher and activist Grace Lee Boggs, including a screening of the documentary American Revolutionary and a conversation with the filmmaker, Grace Lee. Confirmed Keynotes:

We invite proposals that cover topics related to understanding and advancing public philosophy from all walks of life, including those that:

Proposals should specify the format: workshop, paper, organized panel or projects. Workshops. Proposals should include a workshop title and description (~300 words) of the organizer’s or organizers’ interest and experience with the subject matter and how the topic is of concern to philosophy or public life. Proposals should also include an overview of how the two-hour workshop will proceed, highlighting how it will be participatory and indicating any non-academic participants you might invite. We anticipate that workshops will take different formats, depending on the issues being addressed and the number and type of participants. The goals of these sessions are to foster partnerships and projects, whether new or ongoing, and, where appropriate, to spark substantive dialogue between philosophers and “practitioners” (public policymakers, government officials, grassroots activists, nonprofit leaders, etc.). A second call will be issued later in the year inviting people to apply to participate in accepted workshops. (Workshop organizers should help publicize this second call.) We will limit each workshop to about 20 participants. Those who are accepted in time will be listed on the program as discussants, though they will not be expected to make a formal presentation. Papers, Project Reports, or Narratives. We are especially interested in papers that report on public philosophy projects or reflect on the practice of public philosophy. Proposals should include the title and an abstract of no more than 300 words. Individual papers should be prepared for 30 minutes of presentation and discussion time. Accepted proposals will be grouped into sessions. Papers may be presented in any style, from reading whole or sections of papers to more conversation based to PowerPoint slides and multimedia. Organized Panels. We invite proposals for 90-minute panels on any number of themes: Book sessions, philosophical issues in public philosophy, or policy problems and how philosophers have or may engage them. Panels should include a set of three presentations followed by discussion. Proposals should include names and affiliations of proposed panelists, the proposed format, and an abstract of not more than 500 words. Abstracts Due January 31, 2019, please submit to: https://easychair.org/conferences/?conf=ppn2019

0 Comments

Below you will find blogs written by students in my Inside-Out Prison Exchange Course Fall Semester 2017 entitled Philosophy Incarcerated. Each blog was co-written by students who are incarcerated and free. These blogs express their views on mass incarceration and the carceral system (social, psychological, bureaucratic and physical). Topics include solitary confinement, felon disenfranchisement, individual values, retribution and rehabilitation, the lack programs for lifers, and the phenomenology of doing time .

The Socratic Oath is wholeheartedly believing in your personal values and that if you deviate from your beliefs, then you are not truly living. You would rather take the consequences that society gives you because of your actions, instead of bending to break what you believe. Socrates’ beliefs were tested when he was placed on trial for supposedly being an atheist, corrupting the youth, and being considered a nonbeliever of the gods of Athens. Socrates viewed himself as someone who challenged the societal roles of all class levels, as well as the wisdom of others. Socrates did not view himself as an atheist, but rather a believer of more gods than solely the Athenian gods. Because he was teaching youth to question the acceptance of Athenian understanding, he was seen as corrupting them rather than helping them become wiser. We have never had to make the decision that Socrates had to make, however it does remind one to consider the values that you hold and live your life by. A set of values could be a religion or sect, political affiliation, cultural affiliation, or any other kind of doctrine or philosophy. Another avenue of gaining values is to transition from one’s own experiences. A person’s values don’t usually change unless they go through a change of themselves. These could be anything from age to environment. Our stories show different ages, different environments, different challenges, different backgrounds, and different lives. We have all had values and beliefs change in our lives, whether that be when we were younger or through our time of growing up. Our beliefs have become building blocks for our future and how we each live our lives every day. Before Alyssa: For me, I had to grow up quickly because of home circumstances. I have a little brother that I had to help take care of. It always felt like my mom and I had to protect him, since I was unable to have a normal childhood. We desperately wanted that for him. Ang: My experiences as a 20 year old on the outside have been different. I struggled with my image and with success. I thought that my image needed to perfect and I was driven in my actions by what people would think of me. I was the pastor’s kid, the straight- A student, the athlete, and the girl who was always smiling. I tried to do it all and through that, I pressured myself to be successful in each one of my images. Because I pressured myself so far, my smile was hiding pain and hurt that was underneath everything. I didn’t smile because I was happy, I smiled because I couldn’t bear to let others know that I didn’t have myself together. After Alyssa: Because of this, I have always been not only family oriented, but hard-working and determined to create a better life for myself. I am not very old, only 20, so maybe I will change as time goes, but as of now I stand wholeheartedly by my determination, as well as would do anything to take care of my family. I have not changed, but I also think it is because I had to adapt younger than most to an adult mindset. Ang: Looking back now, I know that so much of what I poured my time into was temporary. I had surgery on my back and I was pulled from games, meets, and tournaments until I wasn’t able to play at all because of my injury. I continue to do my best to succeed in school, but my worth is no longer placed on a letter grade. My faith grew to become my foundation and through my beliefs, I now still am the girl that’s always smiling. However, now it is because I have real joy that is so much deeper than just that smile. My values now are my faith, my community, and my happiness. Socrates was incarcerated prior to his execution and he stood true to his doctrine of beliefs. It would have been easy for Socrates to go against his values for his case and especially his release. However, Socrates chose to die for what he believed instead of turning against his own beliefs. Incarceration in our society can be a sentence of social death in itself. When one is given a sentence, you are taken away from your community and completely displaced from everyone and everything that you know. Inmates are stereotypically viewed as soulless numbers in the system. They lose their sense of individuality and humanity, as well. However, what society usually fails to realize is that people change. Years spent incarcerated forces its own kind of change of values for an inmate through the change of age, environment, and challenges. Cole’s and James’ values have changed for both of them because they have been forced to reevaluate pieces of their lives in a new way. Every person grows in their life through how they build their value system and an inmate is not an exception to this. They all have a story to tell and we were able to share all of our stories with each other. Before Cole: As a young adult my values lacked coherence. Before coming to prison I was a drug user and therefore was unable to properly assess the values I held. Much of my adult life before I came to prison, at the age of 27, was spent either in, or right outside of, addicted drug use. Being addicted to a drug, or anything really, warps a person’s mind and renders every priority secondary to that addiction. My family exhibited plenty of values and virtues for me to follow in their footsteps and be a good person, because of this, I at least had a foundation of values that I admired about my family that I could build on. James: I did not always live life with integrity. In my younger years, I was less concerned with how my words would affect others. If deceiving others benefited me, I did. During/After

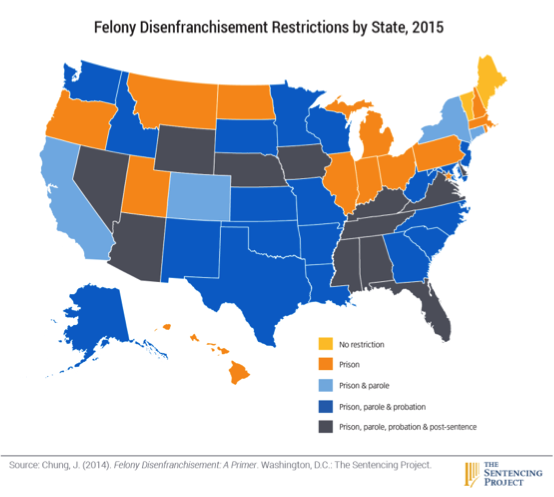

Cole: Once incarcerated, I decided that no matter how long it takes, I have to change this. The second thing I decided was that no matter what the consequences, i can’t let the typical prisoner’s mentality and attitudes become my own. Since being incarcerated, I have felt a need to learn about as many things as I can. I feel that the more information I take in, about any and everything, the more accurate I can be in knowing myself and the world around me. James: After years of incarceration, and of course getting older, I now understand the importance of a belief system. Honesty is at the center of this value system. My word is my bond. Without it I am nothing. I will still always pay the consequences for my actions, even if being untruthful will grant me reprieve. Through being in a class of inmates and students, we have been able to share pieces of our lives with each other. College students have been able to receive knowledge and have one’s eyes opened to a piece of society that so often is tried to be forgotten. Inmates have been able to share their stories with people who have ears to hear, which is not easily found. We all are able to be raw and vulnerable about the brokenness in our world and in our own lives. Socrates taught us to seek out the values that we each have and to remain true to those beliefs. There is not a key set of values that is “correct” and the process of getting to learn about different people’s value systems has made that evident. However, another value that we have learned throughout our time together has been to recognize that everyone’s story is important. Each person has a story to share and sometimes we have to be prepared to listen and to search for the growth that they have come through and which values drive them each day. Image references Image 1 https://purposeandnow.com/2011/02/14/core-values-or-placebos/ Image 2 purposeandnow.com Image 3 http://www.amreading.com/2017/01/23/5-reasons-experience-isnt-necessary-for-writing-a-good-story/ On January 31, 1865, Congress passed the 13th amendment, which states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States...” The immediate implication is that being convicted of a crime entails forfeiture of certain rights guaranteed citizens, including the right to vote. The 15th amendment provides transparency regarding this important contradiction in the legal system. It states that people shall not be denied their right to vote based on their race, color, or previous conditions of servitude. Convicted felons are only allowed to vote once they are released. In fact, in some states, a felony conviction will permanently prohibit the offender from voting. Incarcerated or paroled individuals, on the other hand, are still at the mercy of a system they have no say in constructing or modifying. The inconsistency with the written law is alarming for a few reasons. First, it prevents incarcerated peoples, who have a right to participate, from voting despite the potential for valuable societal and political contributions. As Michael, an inmate at London Correctional Institution (LoCI) points out, disenfranchisement operates to alienate potentially informed voters. “For those of us behind these walls for an extended period, the perspective of our previous world has been drastically changed. Nowhere is this truer than in politics. Whether out of necessity or boredom, we’ve acquired an awareness that we never previously had. Rather than socializing at the bar, cramming for exams, or scouring the web for the latest viral video, we’ve been debating current political issues, intently watching the news, and poring over countless law books. The irony is we have no say.” Enfranchisement would be advantageous not only to inmates, but to society at large. Inmates have firsthand knowledge of the justice and penal systems that most of us do not have access to, and their particular situations provide a new and important perspective on many issues. As Michael says, “Many inmates have become fully conscious of the issues plaguing our nation and our world. We’ve become informed activists, unlike many of our peers in society. Yet we have absolutely zero influence on our local, state, and federal politics while behind bars and little upon release.” Imprisonment forces many inmates to confront the system in new and critical ways. For some, this leads to an evolved worldview and a deeper understanding of their personal convictions. Take Michael, for instance: "I’ve always been a staunch liberal. I’m not suggesting that my status as an incarcerated individual has changed my position. It is simply now I understand why I believe what I do. Although I came to prison at only 19, I never considered the value of taking a stance on an issue. I would drive by picketers and honk for their tree-hugging cause. When my predominantly black high-school football team was denied service at a local McDonald’s, I donned a jersey with the numbers painted black during the next game. I supported a classmate who was transitioning to a female. However, I never really comprehended the significance of these actions. When I was arrested, I was removed from my element and put in an environment saturated with all sorts of men from different socioeconomic classes, cultural and religious backgrounds, and political viewpoints. It forced me to analyze my positions, not only to substantiate my arguments, but to develop tolerance for those who don’t think as I do." Disenfranchisement also sets a dangerous precedent of reinterpretation by the state, effectively limiting the rights of all citizens under the guise of justice. The distinction between actual rights and merely designated conveniences is a fine line, one that has an immense amount of destructive power. To those of us who have never faced incarceration or the jaws of the U.S. legal system, it may seem justified in its own right to strip those who have committed a punishable offense of their freedoms for a period of time as a form of retribution. However, the extensive abuse of power to which inmates are subjected and their lack of means to defend their rights and humanity reflects a far more sinister and cruel system of discipline. This country is founded on a principle of rights and freedoms that encourages a bottom-up approach to governing. Unfortunately this principle only applies when the state arbitrarily deems someone eligible to vote. The right to vote is only limited by an age restriction and status of citizenship, regardless of access to information or interest in policy. Just because a person has rights does not mean they are forced to exercise them at all times. However, someone who has a vested interest should not be denied the opportunity to contribute as long as said thought or action remains consistent with rights bestowed upon them. Yet, as Mike, another inmate at LoCI notes, “We inmates are denied legitimate means of pursuing self-interest.” This prohibition extends far beyond the ballot. Not only are inmates denied the ability to shape institutional policy through the electoral process, they’re effectively denied the capability to exercise the rights they’re guaranteed under current institutional policy. Aware of their perceived lack of credibility, many inmates remain silent in the face of injustice. Kristie Dotson, the brilliant Black feminist and epistemologist, calls this coerced silencing testimonial smothering. It occurs, she says, when a speaker believes his audience is unwilling to accept his testimony (244). Mike provides an example of this silencing in action: Let’s say you go to prison. You have a complaint, so you go to the unit staff’s office. They’re sitting at the desk chit-chatting with each other when they say, “Come back later. I’m busy.” You try to explain your urgency, but they say, “Who the fuck do you think you are, inmate? Can’t you see I’m fucking busy?” You have no choice but to leave. You don’t want to get a conduct report, because it’s nearly guaranteed that you will be found guilty. This could ruin your chance of being paroled. If it’s your word against an officer’s, even one known to have a history of lying and writing frivolous tickets, they will never side with an inmate against another staff member for fear of being fired. Aware of these structural impediments that effectively silence them, many inmates seek other means to solve problems. Mike continues: Say you’re having a problem with another inmate, so you go in the bathroom and punch him in the back of the head while he’s brushing his teeth. You win admiration and get invited to join a gang, giving you access to friends, money, and drugs. You’re safer thanks to your new affiliation. Later, opiates are found in your cell. You know if you get a conduct report, you’ll be found guilty without a fair hearing. So your gang approaches your cellmate and coerces him into taking the rap. He knows you’ll kick the shit out of him if he doesn’t do it. Even if he doesn’t fight back, he’ll be punished for fighting, he’ll still get beat up, and, because nobody admitted to it, he’ll still get a ticket for drugs. So he takes the rap, and you get away with it. That’s his punishment for being a model inmate, while you’re rewarded for being a thug. The silencing of inmates may actually encourage criminality, the very thing the penal system is meant to purge. As Mike put it: Anybody trying to stay out of trouble and become a better person has the system stacked against him. Anybody selling drugs and manipulating authorities gains control over his environment, ensuring his own survival. If I try to influence a newly-convicted young man to do the right thing, I can’t compete with gang members for his attention. Why come work with me to improve themselves when this seemingly gets them nowhere? It’s no different on the outside. My felony status means I’m not allowed to vote for a higher minimum wage, but I can rob a gas station or sell heroin. This is disenfranchisement, and it’s making your community dangerous. While disenfranchisement of inmates is certainly constitutional, we must question if it violates inmates’ fundamental human rights and also if it is in the best interest of society at large. The benefits to enfranchising the inmate population, both by allowing them the right to vote and by taking their testimony in all matters seriously, are two-fold. It would fill epistemic gaps by allowing the particular knowledge of inmates into public discourse, and it could potentially reduce criminality, which is the very goal of the penal system. We leave you with a plea from our friends on the inside: “For the greater good of our nation, we on the inside implore those of you capable to champion for change to contact lawmakers and insist they add this population of informed voters to their constituency.”

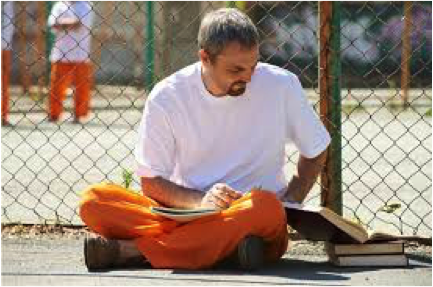

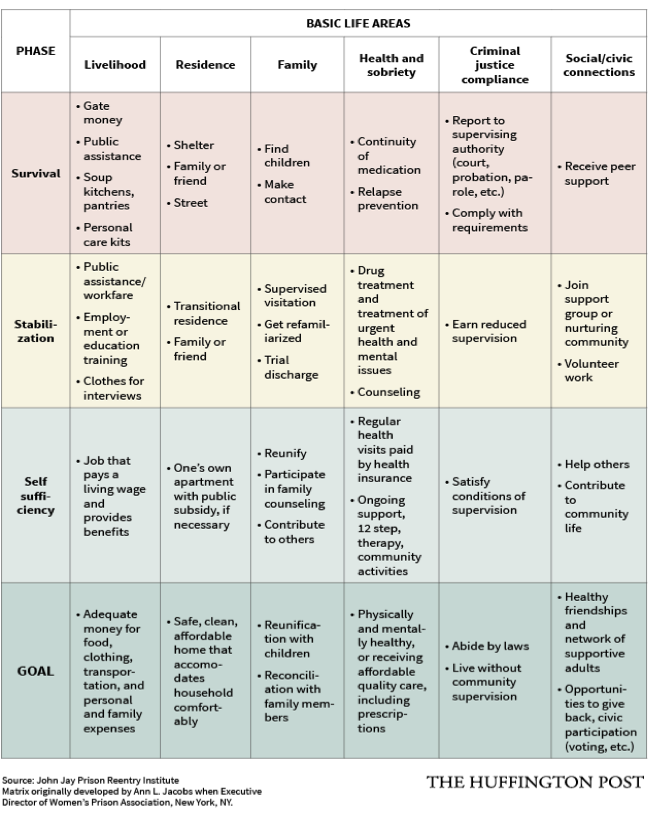

Works Citedand Images Dotson, Kristie. "Tracking Epistemic Violence, Tracking Practices of Silencing." Hypatia, vol. 26, no. 2, May 2011, pp. 236-257. Academic Search Complete. Web. US Const. amend. XIII, sec. 1. US Const. amend. XV, sec. 1. Image 1: http://launch.durangoherald.com/articles/108912-most-jail-inmates-have-the-right-to-vote-but-few-do Image 2: http://drexel.edu/now/archive/2016/January/Prison-Project/ Image 3: http://www.vipublicdefender.com/know-your-rights Image 4: https://race-and-social-justice-review.law.miami.edu/felony-disenfranchisement-presidential-election/ The majority of men who enter into the prison system either have minimal employable skills or have dropped out of school. They commonly have not attained basic reading or writing proficiency and do not hold education in high regard. Coupled with these, most inmates are from racially and economically disadvantaged backgrounds and feed into the confirmation bias of their demographic. Many inmates also suffer from some form of mental deficiency and lack the discipline to want to improve their lives. Thus, the time spent in prison for many is not just physically but emotionally devastating. These issues may be the result of circumstances that often includes poverty, drug use and substance abuse. When a person becomes incarcerated, they enroll into programs that teach interpersonal skills and use individual counseling and behavior modification techniques to assist them for their return to society. Programs like these are invaluable because it is believed that “recidivism rates drop when the education programs are designed to help prisoners with their social skills, artistic development and techniques and strategies to help them deal with their emotions.” (Vacca, 299). When inmates are given the opportunity to improve themselves they prove that they have the capability for reform and the institutional barriers that restrict entry to these educational programs only delay their progress. Unfortunately, while incarcerated there are limited options for inmates when it comes to programs they can get involved in and even when these programs are available, inmates face many restrictions to entry. A majority of the programs offered are strictly for reform and preparation for life after incarceration while others are educational. Thus, as we will discuss later, the targeted demographic is inmates nearing release from prison. There are numerous benefits to providing rehabilitative programming opportunities to inmates, especially those facing longer sentences. Firstly, educational programs that provide training in moral education, critical thinking skills and problem solving skills especially when targeted towards at risk individuals reduces the rate of incarceration (Vacca, 300). Secondly, programs such as career training, substance abuse management and mental health training that help inmates learn how to enter back into society are beneficial because they help inmates upon release to adjust to the qualms of the outside world. Providing classes like the Inside-Out courses helps inmates build “normal” social relationships outside of the people within the compound. because they are interacting with people who are not incarcerated and this interaction could help their stress about their social standing. Thirdly, vocational training programs like carpentry or plumbing help inmates with job preparedness and the feeling of fulfillment. These trade programs should be available to all inmates who are interested in learning said skill. If the three reasons listed above prove unconvincing then the availability of these programs can also reduce problems that can arise when the only thing inmates can do all day is sit around and maybe an hour of yard time. This would keep the inmates busy and less likely to feel constricted and restless. These programs have also been found to be cost effective. In a study done by the RAND corporation, they found that an average program cost $1,400- $1,744 per inmate when reincarceration cost $8,700- $9,700 (RAND). The percentage of prisoners returning to prison after taking vocational or educational programs is 43% less than those who do not. The chart below from the Huffington post article that shows the 6-basic life needs and explains what complete adjustment to life outside of prison can be and what the goal is for most inmates after release. These programs allow that inmates get the best start in the process of re-entering into society. Programs offered at the institution vary due to institutional differences and funding. Their quality also depends on staff attitudes and administration because these people have to be compassionate and genuinely want to see offenders get themselves together. Corrections has changed drastically in the last 20 years with the control of funding, lack of personnel and the generation of individuals coming inside and working in this system. There is so much focus on the punishment and how we can make the offender pay the price for what he/she did wrong that we don’t have a solution to fixing the preexisting problems that brought them to prison. Programs can help if we have compassionate yet unyielding people willing to train and teach the offenders. Prison education program face many setbacks but the most discriminated against is educational programs,

Due to limitations on space, security risks, and limited funding for necessary supplies, some academic subjects are less likely to be incorporated into prison education curricula than others. For example, courses that require science labs, computers, extensive library research, and/or internet access are more challenging courses to offer based on available space and how that space must be modified for the course to take place. These limitations may impact the ability of students to meet certain degree requirements and may even impact the overall program choices about which majors and concentrations may be implemented in the facility (Foster and Sandford, 602). Inmates that attempt to meet degree requirements face a plethora of institutional drawbacks. Since educators serving prisons are often working on the institutions time and at their convenience they are often disrupted to the point where inmates are not able to complete their degree. This is one example of the way inmates are restricted entry into these obviously beneficial programs. Another way is the seclusion of lifers and long-termers from these programs. Below, an inmate at the London Ohio Correctional Institution (LOCI) gives an account of this type of discriminatory behavior towards the “older” prison generation and the negative impact it has on them. Ronnie By 1996, the history of programming and its benefits to inmates had changed under the new law. New programs entitled “re-entry” were created through a section of the 1994 crime bill signed by President Clinton. The only inmates who benefit from these programs are those sentenced after 1996, except for those convicted for capital crimes and rape. Where inmates were given one good day for completing a program in the past, they now receive anything from one, to five good days a month (good day was a day subtracted from an inmate's sentence). For the record, no inmates under the old law are receiving good days for any programs. However, these “re-entry” programs are a joke. They are nothing but programs with the same curriculum of the past programs. The only thing that changed was the title; for instance, Anger Management was now Cage Your Rage, and cognitive behavior programs were either Thinking for a Change or Mental Technology. These “reentry” programs also excluded lifers and long-termers from taking them. In the past, the parole board placed programming as one condition for long-termers and lifers to complete to be a good candidate for parole. All lifers and long-term prisoners who had taken programs before 1996, were being instructed by the parole board to take them again. Their reasoning rests on the fact that programs of the past were not “re-entry” programs and the State only recognizes their qualifications as a prerequisite to release. Despite this, lifers and long-termers continued to be excluded from taking these programs. One reason for this neglect is due to the prisoners Nature of Crime, which makes them a poor candidate for re-entry programs. So staff pacify the long-termers by placing them on waiting list, but at the bottom. Correctional policy makers consider lifer and long-termers at the bottom of their list of priorities they believe their needs in terms of release are less immediate than other prisoners with an actual release dates. If these inmates are approved to take these programs they are forced to wait to take them five years within their release dates. Even then they can be withheld from taking said programs. This is a minor disappointment compared to the disappointment when inmates are told, that their parole is denied even though they completed the programs that the parole board instructed them to take. It has become the norm for the prison administration to exclude long-term prisoners from participating in programs other than correctional industry jobs. Most lifers and long-termers turn to industry jobs to earn money and to use their time in prison productively. Since the correctional agencies see long-termers as a stable, responsible and durable work force, outside businesses such as “Coffee Crafters” and “Yamada” have become a part of the new “Re-entry” program. All rehabilitation efforts towards long-termers have been neglected in order to provide a reliable workforce. Institutional are in place that keep the majority of the prison population from reaping from the benefits of educational programs and the like. Works Cited 1. “Education and Vocational Training in Prisons Reduces Recidivism, Improves Job Outlook.”RAND Corporation, www.rand.org/news/press/2013/08/22.html 2. Ferner, Matt. “These Programs Are Helping Prisoners Live Again On The Outside.” The Huffington Post, TheHuffingtonPost.com, 9 Sept. 2015, www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/if-we-want-fewer-prisoners-we-need-more-compassion-when-they-re-enter-society_us_55ad61a5e4b0caf721b39cd1 3. Vacca, James S. “Educated Prisoners Are Less Likely to Return to Prison.” Journal of Correctional Education, vol. 55, no. 4, 2004, pp. 297–305. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23292095. 4. Foster, Johanna E. and Sanford, Rebecca “Reading, writing, and prison education reform? The tricky and political process of establishing college programs for prisoners: perspectives from program developers”, Equal Opportunities International, Vol 25 Issue:7, pp.599-610, https://doi.org/10.1108/02610150610714411  Imagine a spectrum that society uses to determine the social acceptability or criminality of a person’s actions. On one end, you have what society judges to be righteous, and on the other, you have what society judges to be deplorable. Between those two opposites, you have what society believes to be socially acceptable. By imagining it this way, we can see how people aren’t fully or indefinitely one or the other. People move back and forth, along the spectrum, and we want to argue that incarceration has an effect that on people that pulls them toward the deplorable side. Deplorable…........... …….……….……….*Socially Acceptable* …......... …….……….……….Righteous. |----------------------------------------------------|----------------------------------------------------| . ….... …….……….……….….... …….……….……….….... …….……….……….….... …….… … Before being charged with a crime, there is an implicit judgment that the person being charged falls somewhere in the socially acceptable range of the spectrum (a harsher judgment would place the person closer to the deplorable side). If someone is viewed as extremely righteous, it’s almost inconceivable that they’d be thought of as a suspect for a crime in the first place. Regardless of guilt, people on trial fall somewhere in the middle of the spectrum, so it is conceivable that the accused could’ve done it because they aren’t fully righteous. Prison is supposed to be place that rehabilitates people, pulling them toward the righteous side of the spectrum. Nevertheless, that doesn’t occur within penitentiary walls; the prison system actually has the opposite effect, pulling people toward the deplorable side of the spectrum. In high school, there were cliques like Jocks, Nerds, and The Rich Kids that defined your social status (being cool or not), but that idea doesn’t apply in The Big House. Being in prison deconstructs your idea of what being socially acceptable is, because it removes you from society and removes the social roles that previously made you who you were. Once you go to prison, you lose those parts of your identity because no one cares about what you did before you came to prison. It doesn’t matter if you were good at sports or if you came from a good/bad family. When someone first steps off the bus in iron shackles and is escorted into a single cell to be stripped, they are not only being stripped of their clothing, but they are also being stripped of all of their previous ideas and thoughts about their identity. Everyone thinks they are the Alpha when they first arrive, but that perspective is quickly replaced by their new reality. In his book, The Distressed Body: Rethinking Illness, Imprisonment, and Healing, Drew Leder discusses how the lifeworld of incarcerated people affects their perception. Commenting on lived time and lived space, he discusses how the existential displacement of imprisonment disrupts our methods of experience. Concluding the chapter with a section that examines the origin and initial purpose of the penitentiary, Leder says: “In Guenther’s words, Dickens recognized that ‘in practice this withdrawal from concrete social relations did not establish in prisoners the habits of reflective, penitent souls; rather it brought about a general demolition of their personhood, not an infliction of this or that part of the person, but a generalized incapacitation of their Being-in-the-World.’,” (180). Not only does incarceration reshape the personal identities of inmates, it also reshapes their social perceptions, allowing for people to have more violent inclinations. In this way, being in prison inherently causes the inmates to become more deplorable. Imprisonment reinforces antisocial behavior because even talking to the wrong person can violently backlash against you. The prison environment perpetuates a negative cycle that allows violence to be used as the means of determining social status because the fear of violence causes antisocial behavior, which leads to a loss of personhood, which makes committing acts of violence easier. In prison, the consequences of your actions have very different effects, and even words can get you killed. For example, if you ask someone for a honey bun, and you tell them that you’ll give them another on State Day, but when the day comes and you don’t have it, that means you lied and will never be trusted again. That’s the easy part of this equation. Now when you go to the restroom, you’ll be standing at the urinal and out of nowhere you’re getting punched in the side of the head. Violence is the tool used for resolving disputes in prison because a lot of inmates no longer have a sense of what is socially acceptable or don’t care enough to acknowledge the fact that those kinds of actions are normally thought of as deplorable. Physical violence reverses the order of social status in the penitentiary when compared to outside society. Normally violence is considered a deplorable act, something that would lower your social status, but in prison, violence is used to determine where you fall in the hierarchy. Other inmates don’t care about what you did or who you were before you came to prison, they only care about the amount of violence you are willing to display. When righteous people were given the most social status, the gauge was social acceptability, but with the destruction of that idea, physical violence replaces it, causing the most violent people to gain the highest social status. The more proficient you are at displaying violence, the more respect you garner. After all, respect is not given - it is always earned, the hard-way. Because the idea of social acceptability is nonexistent, there aren’t rules that prevent inmates from doing whatever they want. Think about it- whoever said “no” to the bully on the playground; bullies do as they please, until someone meaner and nastier comes along to scare them off, because, like many prisoners, they operate under the law of violence instead of the unwritten laws of socially acceptable behavior. The law of violence, that is the only Law that applies in here. In order to battle the pattern of criminalistic behavior that is forced upon you, you can’t allow violence to overtake and corrupt your moral code of conduct. By choosing not to act violently, you can reclaim the idea of social acceptability; forever changing your perspective of the world. The destruction of identity, the antisocial nature of the prison, and the prevalence of violence are all ways of dehumanizing inmates, but there are more factors that cause prisoners to be pulled toward the deplorable end of the spectrum. Day in and day out, you are constantly around others who talk non-stop of their crimes, and before you know it, you start to analyze their mistakes and begin to critique them as if you were going to go out and commit the same crime, but only to do it better. Leder comments on Charles Dickens use of Plato’s cave from the Republic as a metaphor for a prison cell by saying:

“Though metaphorical, it seems an apt image of many a prison. Educators, counselors, and others who might bring “light” from the outside world are often woefully absent. The inmates are left primarily amongst “shadows” - the society of often contemptuous authorities, other criminals, and personal memories of a previous misspent life. For most, there are few activities of a positive nature to pursue. The entire environment reinforces their identity as a “criminal,” taking an act from their life, perhaps the worst thing they have ever done, and saying “this is who you are.” Not surprisingly, on release from the cave, the inmate is often poorly equipped to reenter the broader society,” (181). For inmates, topics of conversation often revolve around criminality. Constantly being subjected to those ideas keeps them fresh in your mind, and it gets your imagination moving in the wrong direction. The prison environment doesn’t present positive opportunities for inmates, and in many ways it reinforces criminal behavior. Prisoners are denied access to educational resources and the necessary psychological therapy that would allow them to improve themselves, making it difficult to move toward the righteous side of the spectrum. Prison environments reinforce criminalistic behaviors because it inherently destroys your identity, sense of self, and your social conceptions. In society outside of the carceral system uses a spectrum that contrasts the righteous with the deplorable in order to determine what is socially acceptable. Because prisoners often use violence as a means of creating a social hierarchy, they don’t follow the normal conceptions of socially acceptable behavior, which reinforces further the criminalistic patterns they are forced into. This process of being pulling toward the deplorable end of the spectrum is, by nature, the opposite of what rehabilitation is, so therefore, rehabilitation doesn’t really exist or operate in our current prison system. References images: Jock => https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/heres-where-your-online-hiring-efforts-go-horribly-wrong-leigh-davis Prisoner behind bars => https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/nov/02/prison-violence-crisis-talks-elizabeth-truss-union-calls-off-protests Knife/Shank => https://d2v9y0dukr6mq2.cloudfront.net/video/thumbnail/A0c7kEP/videoblocks-male-prisoner-adult-white-caucasian-holding-a-knife-shank-weapon-contraband-violent-gang-member-orange-jumpsuit-violent-young-offender-20s-30s-serving-time-in-county-jail-convict-in-prison_r7gfugwce_thumbnail-full01.png  ‘ Image provided by the Pinellas County Sheriff's Office, retrieved from nbcnews.com 'Solitary confinement’ is a phrase that many people who are not and have never been incarcerated have heard, but do not think much about. They don’t really know what it means, or what people in long-term solitary confinement go through both physically and psychologically. They just know that some prisoners are separated from the rest of the prison, presumably for doing something wrong. This is not always the case, though. Sometimes prisoners are held in solitary confinement simply because of overcrowding in the rest of the prison. All of this is not to say that no one unassociated with prisons know what it is, but prisons generally do not advertise the negative effects solitary confinement has on prisoners. Image provided by the Pinellas County Sheriff's Office, retrieved from nbcnews.com Solitary confinement cells range from the size of an average Porta-Potty to about the size of a school bus (Dawson 2014). Cells include a bed, desk, chair, and toilet which are all fixed to the floor. They sometimes include a television with minimal channels. Many do not even have windows, but prisoners are kept there, alone, for 22-24 hours per day. They are dependent on their guards, who push food, mail, and toilet paper through a slot in the door of their cells. The only interaction inmates are allowed with other people are with these guards who, to understate things, do not treat them very well. Inmates in solitary confinement can talk to other prisoners, but only if they shout through their cell doors or walls. Some are let out of their cells for an hour or two to shower and/or exercise, but this is not always the case. Even if they are let out, it is often only while wearing handcuffs and shackles and under constant supervision by at least one guard. This type of environment drives people crazy. Humans are social creatures and need to interact with other people to keep their mental states intact. Long-term solitary confinement seems to make many mental illnesses worse, if not cause the onset of new ones. Prisoners often suffer from depression, apathy, hallucinations, panic attacks, paranoia, hypersensitivity to external stimuli, dissociation, and psychosis, just to name a few (Gawande 2009; Rhodes 2005). Those in long-term solitary also report they have difficulties with thinking, concentration, and memory. They may have trouble sleeping, dizziness, heart palpitations, or become violent (Gawande 2009). Photograph by Dan Winters, retrieved from gq.com

In this way, one thing solitary confinement is supposed to deter—violence—is actually caused by it. One study in Washington State found that 10% to 15% of the state’s prison population was mentally ill, and another, similar study found that 20% to 25% of supermaximum security solitary confinement prisoners were mentally ill. This huge difference is partially because when prisons run out of beds in their psychiatric facilities, they house mentally ill patients in solitary confinement, and partially because solitary confinement breaks people psychologically (Rhodes 2005). Let me try to put into perspective how terrible conditions are for people living in solitary confinement. The executive director of the Colorado Department of Corrections, Rick Raemisch, put himself in solitary confinement to see what it was like. He was having doubts that solitary confinement was working like it was supposed to, so he decided he would test it out himself. After just twenty hours, he was so troubled by the experience that he let himself out. This year, he succeeded in ending long-term solitary confinement in Colorado. In 2015, the State Department and other United Nations countries ruled that keeping someone in solitary confinement for more than 15 days was torture (Raemisch 2017). So, why, then, do we still allow (and sometimes even encourage) prisons to keep their prisoners in solitary confinement for decades? People’s answers to this question can be monotonous and contain multiple perceptions with biased opinions. Let’s steer away from opinions before we find ourselves talking in circles and accomplishing nothing, while others suffer in isolation due to our disingenuous discourse. To avoid such disingenuous discourse, I suggest we start with trying to understand humanity, beginning with humanity’s biological “fight or flight” instinct and its relation to one’s “comfort zone” One reason we allow oppression to persist is because of our own self-interest. Our value system is based on economic safety, which drives our emotional interest toward utilitarianism. Based on this emotional drive, we can see how economic interest best serves self-interest. Distancing ourselves from policy that affects the less fortunate strengthens the overall interest pertaining to the greater good of the most fortunate. Assuming this to be true, there’s no interest in prisoners unless you are one, you have some association to individuals in the industrial prison system, or you legislate the bureaucratic prisons system. If you are a prisoner or have a loved one who is, the interest is evident. They are motivated by one day seeing the prisoner’s release as well as making sure their well-being is being looked after. Politicians and private industries have a sociopolitical and economic interest in prisons, and thus prisoners are commodities to them. As commodities go, prisoners are the bedrock of the capitalist system. Aside from the sociopolitical parties, a majority of society is complicit in the ideals and implementation of solitary confinement. Our self-interest allows solitary confinement to be the norm behind prison walls because it is within our comfort zone. Amongst the disingenuous murmurs, we justify our arguments by saying solitary confinement provides an added level of protection for the public, offers prison safety, and aids in reformation of prisoners’ characters. This is simply not true, because as mentioned earlier, studies show that solitary confinement overwhelmingly makes the prisoner more violent. However, this argument doesn’t contain the moral and ethical might that is needed to conjure some emotional blitz. The emotional detachment in society are the results of self-interest, which affects the whole by deconstructing a cohesive into an individual with his or her own self-interest. This interest satisfies a hierarchy of needs, thus changing his or her level of comfort. As long as this comfort is undisturbed we are more than happy with going along with the status quo. Discussing the abolishment of solitary confinement disrupts the status quo. Most of us don’t want to fight, so flight is the easiest recourse. The temptation to be different poses that you much jump out of your comfort zone, pending your stamina. Tackling the issue of solitary confinement is the starting point prompting prison reform to the finish line. While tackling the issue of solitary confinement, we are metaphorically asking the body (society) to “fight” rather than the easier “flight” response. When society fights for change, things can get ugly. The human nervous system will respond as if immediate threat is upon it; the body tenses up and spends a quick amount of energy to oppose forces restricting its movement in space. Spending this energy has to come to an end, however, because they body cannot sustain this trauma. Once the energy is spent, the body goes back into a relaxed state triggered by exhaustion or lack of stimuli. The reality of discussing solitary confinement issues correspond with the cause and effects represented by the human nervous system. Once that relaxed state is achieved, the comfort zone resumes even if the aftermath is ugly, because the stimulus is no longer there or inert. Recently, we’ve experienced this phenomenon in the forms of state elections, a five-day news cycle that reported problems with overpopulated prisons, unemployment dropping to 4%, and after a newly released prisoner committed a heinous crime while under parole supervision. The latter example is also an example of the “I told you so” phenomenon. As a result, all of the fight is exasperated and old ideas to prevent traumatic events reemerge like the “walking dead,” clawing up from beneath the scourged earth. A variable of comfort is “flight.” On one hand, flight is pushing our emotional environment further away from traumatic thoughts—prisoners suffering from depression and/or hypersensitivity to external stimuli due to solitary confinement—therefore enforcing our state of rest. On the other hand, we are also isolated and cannot achieve real growth because staying in flight smothers the growth of the sprout from the scourged earth. The only way to achieve growth is to move from the graveyard of sterile ideas and challenge our resilience by being uncomfortable. When we are at peace with our decisions as a society—changing policies based on reoccurring symptoms—the same is reflected as an illusion of security unlikely to spur motivation. Here entails the contradiction between peace with our decisions and comfort within our decisions. Peace is a fruition constituted by growth, and comfort is a state of rest lacking motivation. The lack of motivation continues to restrict genuine prison reform as it relates to solitary confinement. References Dawson, L. (2014, December 19). Infographic: How Big is a Solitary Confinement Cell? Retrieved November 13, 2017, from http://solitarywatch.com/resources/multimedia/infographics-2/how-big-is-a-solitary-confinement-cell/ Gawande, A. (2009, March 30). Hellhole. The New Yorker. Pinellas County Sheriff's Office. (2014, March 1). [Photograph found in Movement to End Solitary Confinement Gains Force]. Retrieved November 14, 2017, from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/movement-end-solitary-confinement-gains-force-n38521 Raemisch, R. (2017, October 12). Why We Ended Long-Term Solitary Confinement in Colorado. The New York Times. Rhodes, Lorna A. (2005) “Pathological Effects of the Supermaximum Prison.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 95, no. 10, Oct. 2005, pp. 1692–1695., doi:10.2105/ajph.2005.070045 Winters, D. (2017, March 2). Untitled [Photograph found in Buried Alive: Stories From Inside Solitary Confinement]. Retrieved November 14, 2017, from https://www.gq.com/story/buried-alive-solitary-confinement  By: Nate, Rob, Key, and Maklayne When surveying the present day American prison system, one can confidently say that retribution is the philosophy and model upheld by most prisons. Although, it has not always been this way. Most European prisons were founded not to incarcerate, but to rehabilitate and punish, often through labor or work under the person one committed the crime against. Prisons themselves were built to hold someone for a short period until their punishment was finalized, they were never meant for extended holding or making people trade in life time for redemption. 18th century America brought a change to the prison system through the Pennsylvania Quakers, who believed that crimes needed to be paid for in a more serious manner. They piloted the combination of serving extended time in a prison while also completing hard labor (Barnes 37). Over time this system expanded and became widely accepted—soon separation by isolated cells became part of the principles, and the incarceration structure we know now was born. Today, incarceration around the world takes on many different shapes. America’s system still operates under the 18th century retribution ideal, but many countries have updated their structures and see those incarcerated as people worthy of rehabilitation. Norway, for example, uses the concept of “restorative justice.” They do not have bars on windows, the guards are friends of the inmates, and they work on setting up a successful life after prison (Benko). A problem with the Norwegian system, however, is that the maximum sentence is only 21 years (with a review at the end of the 21 years that can add more time in five-year increments). So, when it comes to cases like that of Anders Behring Breivik, who killed 77 people in a domestic terrorism attack in Oslo, it is often debated whether 21 years of solely rehabilitation based incarceration is truly enough. Retribution versus rehabilitation systems of imprisonment has been a hot topic in the United States for years. It is debated whether rehabilitation is an adequate way to make someone understand the severity of their crimes or if retribution must always be involved. Is one better than the other, or must they be used together to “change” someone? Maklayne: Why do you see rehabilitation as the superior method of incarceration? Nate: The ultimate goal of our legal and penal systems is not to punish offenders for their crimes but to deter crime itself. I’m sure if one asked the victims of a crime if they would prefer to punish the offender of that the crime had never occurred in the first place, they would certainly choose the latter. Retribution is a legalized violence based on a hardwired moral sentiment to punish wrong doers. It works quite well at a tribal level of social organization in which any behavioral divergences or social destabilization likely leads to demise of the entire group, but with the exception of a few dozen indigenous tribes, humankind now lives in a global, technologically advanced civilization which is a far different environment that the ones our ancestors in the Pleistocene epoch evolved from. We have developed sciences which show that antisocial behavior is caused by a host of biological and social factors, yet those who propound retribution still rely on primitive fold psychologies which assign all moral responsibility to the individual based on groundless metaphysical suppositions such as self, free will, sin, etc. Also, our modern culture has the necessary infrastructure and technological know-how to modify behavior for the purpose of deterring crime without recourse to violence. To retain the outmoded social practice of retribution is now not only barbaric it is also ineffective. Multiple studies show rehabilitation model reduce recidivism whereas retribution only further acerbates the offender’s antisociality and contempt for authority. Two categories of criminal in particular demonstrate the superiority of rehabilitation over retribution. In the case of drug addicts and child molesters, the use of punishment to deter future offenses is utterly useless. The former, regardless of their good intentions, are incessantly compelled to satisfy their addiction despite the likely consequences of imprisonment, poverty, ill-health, and even death. The main mechanisms behind their addiction are chemical, to use anything else but a chemical cure is futile. Psychotherapy, a prayer, nor prison time will have much effect on their brain’s chemical dependence. The latter are even more resistant to retribution as in most cases their proclivity to molest children is intertwined with their psychosexual development. Many offenders were themselves victims of sexual abuse as children which later shaped their beliefs and behaviors regarding sex. How do you use punishment to modify a sexual fetish that emerges from trans-generational abuse and other sexual deficiencies? To use retribution to change such behavior is akin to “praying the gay away”. Only a rehabilitation model can hope to address this problem along with the entire spectrum of criminality.  Rob: Nate was asked, “Why do you see rehabilitation as the superior method of incarceration?” Which he responds with nothing more than rhetoric. Albeit a lengthy response to but a simple question, like any politician he wants you to become lost in an enchanted forest of words. First, Nate attacks the moral and metaphysical ideas underlying retribution but does not mention similar presuppositions underlying rehabilitation. As he says, “Retribution is a legalized violence based on a hardwired moral sentiment to punish wrong doers.” I say, is rehabilitation not a “legalized violence based on a hardwired moral sentiment” to force people into the mold of socially defined normality? M: Do you believe that a rehabilitation model of incarceration is enough for someone who has committed a serious crime like rape or murder? Would retribution need to be involved as well? N: Your question begs another: What does one mean by enough? It is imperative for society to engage this question if its carceral systems will be able to achieve some semblance of logical coherence and practical effect. From a retributive perspective, “enough” signifies a quantity or quantum of justice in the form of deprivation, abuse, pseudo-moral instruction, financial restitution or simply time. Now from a rehabilitative perspective, the question of enough implies a skepticism of any methodology that eschews violence to modify behavior. This is based on a general ignorance of the mechanisms behind human psychology as well as the new technologies we’ve developed to manipulate those mechanisms. Retribution is the first and last resort of those policy makers who don’t really understand crime or for that matter, human nature either. They can only use the primitive tools of pleasure and pain to produce an effect. Proponents of rehabilitation, in contrast, has access to a mountain of data collected from several fields of research which they can then use to design their models. So, your question should be revised as: Is our species civilized enough to properly manage its social deviants? R: Nate did not even answer the question. He speaks of the need to define the word “enough” but fails to provide the positive definition he needs. He defines it negatively by contrasting it with retribution’s quantified sentences but fails to provide any meaningful alternative, true politician magic, in circles we go. Keylahn: Rehabilitation is the re-integration of a convicted person into society. Would you say that prisons are working towards this for most prisoners? Rob: The answer to this question is yes, for the past several years as it pertains to Ohio’s prison system. There are now several re-integration prisons. Further, Ohio operates on a security threat level. Level one’s are the lowest threat while level 5 are the highest and considered the most dangerous inmates and are constantly under scrutiny. Ohio has been working to help these inmates that may be released soon to lower their security level to a level 1 or 2 in order to be moved to a lower security prison; minimum security prisons for level ones are usually medium prisons as well for level 2 inmates. Here these inmates have plenty of movement ability compared to a close (level 3) or maximum (level 4) and super max (level 5). This allows inmates to redevelop social skills before returning to society, and if at all possible to take a re-integration program before their release. Nate: Despite Ohio’s new tier system, rehabilitation as practiced in these prisons is simply an exercise of going through the motions in order to fixate larger and larger sums of federal assistance ($$$$$$$). My opponent praises the elbow room and other benefits of these lower security level they still operate on the principle of retribution. The staff at these prisons still carry and use pepper spray and hand-cuffs. They also use threatening language and physical violence to intimidate inmates into submission. K: How would you say that rehabilitation and punishment are related? When they are two distinctly different things?

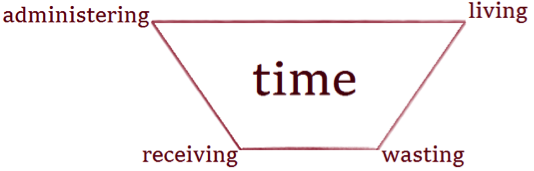

R: Punishment is considered retribution in principle; however, when talking about rehabilitation in the prison system I believe under utilitarian principle, the two are nearly identical in character. Retribution seeks to punish purposely through pain to create deterrence, and incapacitation to protect society in order to achieve justice. Prison rehabilitation does not seek pain as in retribution, however, through rehabilitation pain is created as a byproduct, this occurs when rehabilitation incapacitates an inmate in order to rehabilitate while it protects society which, also creates deterrence. Although retribution deliberately creates pain as its punishment for justice, rehabilitation also subjects persons to pain. Both incapacitate, create deterrence and protect society in their views for justice, the only difference is where rehabilitation concerns itself with what to do with the inmate while incapacitated. Therefore, the two opposite sides of the justice spectrum are very similar. N: My opponent’s insistence that incapacitating people is in all casesa form of punishment boggles my mind. A parent who assigns a curfew to a child does so to protect not punish. Medical authorities that quarantine a sick population do so to arrest spread of a disease not punish the afflicted. Placing a senior citizen in a nursing home is to ensure them a certain quality of life not punish them. The incapacitation used by rehabilitation models is not to punish the offender but to protect the citizens. Rehabilitation and retribution models are fundamentally incongruent. There were obviously some interesting points they both made concerning the similarities and differences between retribution model prisons and rehabilitation model prisons. They could both be argued for as the right or wrong way of running a prison system. Although both gave valid reasons to their arguments Nate’s argument for that they cannot be performed together is the truth. It is almost impossible to have a prison that can perform both in the same vicinity. They are two completely different forms of running a prison, and the retribution model prison had been ingrained so deeply into our culture that different aspects of the retribution model even spills over into the culture of rehabilitative prisons. The rehabilitative model prison and retribution model prison cannot be performed together. Works Cited Harry Elmer Barnes, Historial Origin of the Prison System in America, 12 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 35 (May 1921 to February 1922) Benko, Jessica . “The Radical Humaneness of Norway’s Halden Prison.” The New York Times, 26 Mar. 2015. Uneven Manipulations of Perceived Time Hilario, Sarah, Earl, Ben Figure 1. The beneficial time awarded to the courts and prison guards is stacked higher, peering above the unwillingly manipulated time of the inmate. Lived Experience of Prison Prisons were created to serve as an area of reflection outside of society on one’s self and their actions, preparing them to reenter society better off. Today, it is very rare for an individual to come out better, even if they better themselves mentally and emotionally in a system that works against them, they are still not better socially, now intertwined with the stigma of a “prisoner.” Many who enter prison must adapt to survive how they see fit, possibly committing themselves to gangs or attempting to go under the radar of other inmates or guards. These adaptations made for the “best” survival within the prison are often simultaneously maladaptations to survival in the real world, which is counterintuitive to the supposed original goal of prisons. One of the most detrimental maladaptations for inmates is their perception of time. Time is a constant that does not bend under man’s will, but everyone knows how easy it is to manipulate one’s hours into perceived minutes enveloped in their pleasures, and the opposite in their pains. It will be argued that time is used to benefit institutional officials and detriment inmates. Figure 1 shows the dichotomous manipulations of time affecting officials and inmates as explained by the collaborative perspective of multiple Wittenberg students and incarcerated men. While courts administer sentences nearly at will, along with the arbitrary amount of solitary confinement, they detach themselves from the lived experience of receiving that time. They also live their time during that period as they wish, rather than aim to waste the day away, every day, for the foreseeable future because one is on pause from their life. Trying to Live Your Time Whether one see’s their actions as written in the stars or self-determined, having the ability to decide how your day is spent is a privilege not fully appreciated today. In a typical day, someone can pick and choose, to an extent, what work they do, who they have meetings with, who they interact with, and this allows them to feel like they have power over not only their life but the path it is headed. One needs to continually adapt to plan their time better, whether that better is allowing for more career or hobby focuses, to feel more satisfied with their outcomes. This reality freezes after becoming incarcerated, essentially pausing one’s entire time while depriving it of nutrients, allowing it to be returned too after deteriorating for a period of time. As outside and inside colleagues, we agree that incarcerated individuals may see this time as a chance for a transformative experience, but that usually only occurs when an individual has a long sentence and comes to a realization on how they need to spend that time. When someone has a short sentence, it is easy to get caught up in mere survival within the prison and put little transformative thought into what they can do to make sure they don’t end up back where they are. When one is incarcerated, one’s whole concept of time is reversed. Instead of finding ways to make more time to complete goals and tasks, one completes goals and tasks just to waste time. The first thing one does is create a routine that is done every day just to get through the day and from one day to the next. Inmates do this by breaking up their days in parts like count times, meal times, or movies and shows on T.V. Each time a part of the day is reached, the next part is looked to until the day’s ends and is started over each day. If you are not used to jail or prison, this can be difficult because you are going from the mindset of making the most out of a day to making the day disappear as fast as possible. This makes time seem to go very slow. After months of teaching yourself to avoid time and immersing yourself in tasks that take up large amounts of time, you adapt to a lifestyle in which you waste time for a living. For those who have a long sentence, this becomes second nature. What does this do to someone when they are reintroduced to the outside world and their perception of time is based upon wasting rather than living it? What about the habits they have formed from that perception? How much trouble could it be to try to make appointments when you’ve lost the habit of time management? How many times would someone forget to consider traffic and travel time, or even just acting with a sense of urgency? Receiving Dead Time While doing time as a prisoner, as I have, there are institution schedules such as count, chow, and when one can participate in recreation (rec), and there is your own schedule you construct around the institutional schedule such as walk the yard, work out, and go to school, etc. Once you have the schedules down, every day becomes repetitive. Repetitive to a point where it feels like your life is unimportant and you have no purpose. Being blocked from engaging with the world in a meaningful way, the living, sensing, thinking, speaking person can turn against itself, buckling the hinges of its relational beings (Guenther). When someone feels like that, it can lead to boredom and rage, and those two things mixed together can lead to violence and rule breaking. If one is not mentally strong enough to withstand the boredom, it will create the desire to do something, anything, to stimulate and change one’s current mindset. I have personally fell victim to my boredom and found myself where most people don’t want to be: solitary confinement. Just when you thought your life has already been stretched to the max, this stretches time from seconds to minutes to hours to years. When you first enter solitary, you are placed in a holding cell and stripped naked for “security reasons,” yet it’s just another way to dehumanize individuals. In solitary, breakfast is at 6:30 AM, lunch at 10:30 AM, and dinner at 6:30 PM. Between lunch and dinner forever. There is no sleeping through these hours because people are constantly yelling at one another desperately seeking attention and the guards continue to open the doors and slam them shut. Finally, a person can only sleep so long unless on medications offered by the institution, and honestly you don’t want to be a part of that. The medication here has severe long-term effects. Moreover, everything about receiving time, as far as prison goes, is simple: it’s pure, dehumanizing misery. As an outside student, I, too, have a minor understanding of how institutional forces can justify imposing unreasonable things: institutions trusted to be “reasonable” may be anything but. Emotions are not innate things, but things we learn about others, things swayed by our affective state (Barrett). What seems rational to an individual, including individuals governing our carceral systems, will be shaped by their emotions, and their emotions in turn by their memories, state of mind, and state of body. Civic institutions, including the carceral system’s, rely upon their ability to appear as dispassionate and impartial: emotion being key to rationality casts doubt on that appearance. Applied to sentencing, the idea that a person may receive a harsher or softer punishment, or be granted or denied parole, for reasons other than those based in facts and data is a repulsive idea that feels like a fact of our institutions’ current functionality. Barrett’s own studies found various institutions’ parole boards to be much less likely to grant parole in a hearing held shortly before noon, after controlling for all factors except hunger of those making the decisions. A “gut feeling” against a parolee may be based on nothing but hunger and a mistake. This mistake, in this case, has deleterious consequences for those subjected to state power. In my own experience, my own arrest and trial were subjected to these presumptions, as well, though not to the same extent as my incarcerated colleagues. Individuals’ freedoms may be denied for unrelated and unjustified whims, and this is reason for grievous concern. Call to Action In the previous entries, we acknowledge anecdotal and personal cases whereby reasonable, thinking individuals have experienced harmful consequences of the exercise of state-sanctioned power. We propose that it is our civic duty to reject this arbitrary and abusive use of power, as well as demand that institutional officials justify their sentencing, solitary, programming, and parole decisions in concrete terms. Inmates need beneficial ways to serve their time, rather than waste it away, should we want prisons to be truly correctional or rehabilitative. All other overtures are empty punitives. Works Cited Barrett, Lisa Feldman. How Emotions Are Made: the secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017. Guenther, Lisa. Solitary confinement: social death and its afterlives. University Of Minnesota Press, 2013. |

AuthorI'm a philosopher, a writer, a thinker, an Inside-Out Prison Exchange Instructor. I do a lot of these on the road as part of recognizing the value of philosophy as a public practice. Archives

October 2018

Categories |

Wittenberg

|

Buy Now |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed