|

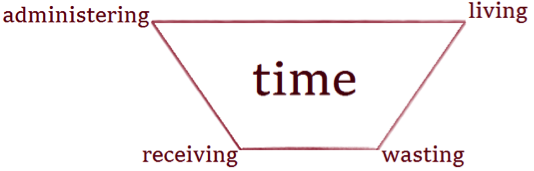

Uneven Manipulations of Perceived Time Hilario, Sarah, Earl, Ben Figure 1. The beneficial time awarded to the courts and prison guards is stacked higher, peering above the unwillingly manipulated time of the inmate. Lived Experience of Prison Prisons were created to serve as an area of reflection outside of society on one’s self and their actions, preparing them to reenter society better off. Today, it is very rare for an individual to come out better, even if they better themselves mentally and emotionally in a system that works against them, they are still not better socially, now intertwined with the stigma of a “prisoner.” Many who enter prison must adapt to survive how they see fit, possibly committing themselves to gangs or attempting to go under the radar of other inmates or guards. These adaptations made for the “best” survival within the prison are often simultaneously maladaptations to survival in the real world, which is counterintuitive to the supposed original goal of prisons. One of the most detrimental maladaptations for inmates is their perception of time. Time is a constant that does not bend under man’s will, but everyone knows how easy it is to manipulate one’s hours into perceived minutes enveloped in their pleasures, and the opposite in their pains. It will be argued that time is used to benefit institutional officials and detriment inmates. Figure 1 shows the dichotomous manipulations of time affecting officials and inmates as explained by the collaborative perspective of multiple Wittenberg students and incarcerated men. While courts administer sentences nearly at will, along with the arbitrary amount of solitary confinement, they detach themselves from the lived experience of receiving that time. They also live their time during that period as they wish, rather than aim to waste the day away, every day, for the foreseeable future because one is on pause from their life. Trying to Live Your Time Whether one see’s their actions as written in the stars or self-determined, having the ability to decide how your day is spent is a privilege not fully appreciated today. In a typical day, someone can pick and choose, to an extent, what work they do, who they have meetings with, who they interact with, and this allows them to feel like they have power over not only their life but the path it is headed. One needs to continually adapt to plan their time better, whether that better is allowing for more career or hobby focuses, to feel more satisfied with their outcomes. This reality freezes after becoming incarcerated, essentially pausing one’s entire time while depriving it of nutrients, allowing it to be returned too after deteriorating for a period of time. As outside and inside colleagues, we agree that incarcerated individuals may see this time as a chance for a transformative experience, but that usually only occurs when an individual has a long sentence and comes to a realization on how they need to spend that time. When someone has a short sentence, it is easy to get caught up in mere survival within the prison and put little transformative thought into what they can do to make sure they don’t end up back where they are. When one is incarcerated, one’s whole concept of time is reversed. Instead of finding ways to make more time to complete goals and tasks, one completes goals and tasks just to waste time. The first thing one does is create a routine that is done every day just to get through the day and from one day to the next. Inmates do this by breaking up their days in parts like count times, meal times, or movies and shows on T.V. Each time a part of the day is reached, the next part is looked to until the day’s ends and is started over each day. If you are not used to jail or prison, this can be difficult because you are going from the mindset of making the most out of a day to making the day disappear as fast as possible. This makes time seem to go very slow. After months of teaching yourself to avoid time and immersing yourself in tasks that take up large amounts of time, you adapt to a lifestyle in which you waste time for a living. For those who have a long sentence, this becomes second nature. What does this do to someone when they are reintroduced to the outside world and their perception of time is based upon wasting rather than living it? What about the habits they have formed from that perception? How much trouble could it be to try to make appointments when you’ve lost the habit of time management? How many times would someone forget to consider traffic and travel time, or even just acting with a sense of urgency? Receiving Dead Time While doing time as a prisoner, as I have, there are institution schedules such as count, chow, and when one can participate in recreation (rec), and there is your own schedule you construct around the institutional schedule such as walk the yard, work out, and go to school, etc. Once you have the schedules down, every day becomes repetitive. Repetitive to a point where it feels like your life is unimportant and you have no purpose. Being blocked from engaging with the world in a meaningful way, the living, sensing, thinking, speaking person can turn against itself, buckling the hinges of its relational beings (Guenther). When someone feels like that, it can lead to boredom and rage, and those two things mixed together can lead to violence and rule breaking. If one is not mentally strong enough to withstand the boredom, it will create the desire to do something, anything, to stimulate and change one’s current mindset. I have personally fell victim to my boredom and found myself where most people don’t want to be: solitary confinement. Just when you thought your life has already been stretched to the max, this stretches time from seconds to minutes to hours to years. When you first enter solitary, you are placed in a holding cell and stripped naked for “security reasons,” yet it’s just another way to dehumanize individuals. In solitary, breakfast is at 6:30 AM, lunch at 10:30 AM, and dinner at 6:30 PM. Between lunch and dinner forever. There is no sleeping through these hours because people are constantly yelling at one another desperately seeking attention and the guards continue to open the doors and slam them shut. Finally, a person can only sleep so long unless on medications offered by the institution, and honestly you don’t want to be a part of that. The medication here has severe long-term effects. Moreover, everything about receiving time, as far as prison goes, is simple: it’s pure, dehumanizing misery. As an outside student, I, too, have a minor understanding of how institutional forces can justify imposing unreasonable things: institutions trusted to be “reasonable” may be anything but. Emotions are not innate things, but things we learn about others, things swayed by our affective state (Barrett). What seems rational to an individual, including individuals governing our carceral systems, will be shaped by their emotions, and their emotions in turn by their memories, state of mind, and state of body. Civic institutions, including the carceral system’s, rely upon their ability to appear as dispassionate and impartial: emotion being key to rationality casts doubt on that appearance. Applied to sentencing, the idea that a person may receive a harsher or softer punishment, or be granted or denied parole, for reasons other than those based in facts and data is a repulsive idea that feels like a fact of our institutions’ current functionality. Barrett’s own studies found various institutions’ parole boards to be much less likely to grant parole in a hearing held shortly before noon, after controlling for all factors except hunger of those making the decisions. A “gut feeling” against a parolee may be based on nothing but hunger and a mistake. This mistake, in this case, has deleterious consequences for those subjected to state power. In my own experience, my own arrest and trial were subjected to these presumptions, as well, though not to the same extent as my incarcerated colleagues. Individuals’ freedoms may be denied for unrelated and unjustified whims, and this is reason for grievous concern. Call to Action In the previous entries, we acknowledge anecdotal and personal cases whereby reasonable, thinking individuals have experienced harmful consequences of the exercise of state-sanctioned power. We propose that it is our civic duty to reject this arbitrary and abusive use of power, as well as demand that institutional officials justify their sentencing, solitary, programming, and parole decisions in concrete terms. Inmates need beneficial ways to serve their time, rather than waste it away, should we want prisons to be truly correctional or rehabilitative. All other overtures are empty punitives. Works Cited Barrett, Lisa Feldman. How Emotions Are Made: the secret life of the brain. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017. Guenther, Lisa. Solitary confinement: social death and its afterlives. University Of Minnesota Press, 2013.

1 Comment

|

AuthorI'm a philosopher, a writer, a thinker, an Inside-Out Prison Exchange Instructor. I do a lot of these on the road as part of recognizing the value of philosophy as a public practice. Archives

October 2018

Categories |

Wittenberg

|

Buy Now |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed