|

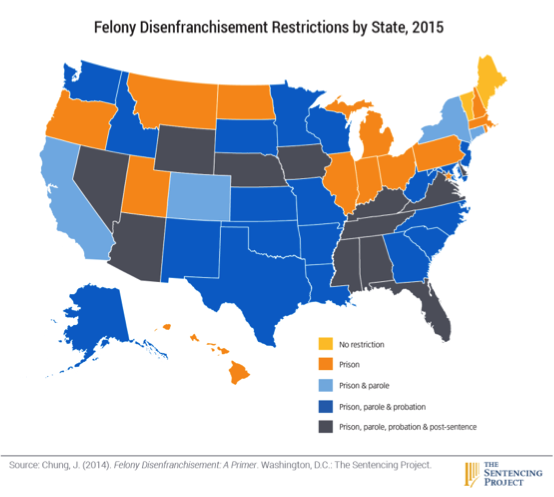

On January 31, 1865, Congress passed the 13th amendment, which states, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States...” The immediate implication is that being convicted of a crime entails forfeiture of certain rights guaranteed citizens, including the right to vote. The 15th amendment provides transparency regarding this important contradiction in the legal system. It states that people shall not be denied their right to vote based on their race, color, or previous conditions of servitude. Convicted felons are only allowed to vote once they are released. In fact, in some states, a felony conviction will permanently prohibit the offender from voting. Incarcerated or paroled individuals, on the other hand, are still at the mercy of a system they have no say in constructing or modifying. The inconsistency with the written law is alarming for a few reasons. First, it prevents incarcerated peoples, who have a right to participate, from voting despite the potential for valuable societal and political contributions. As Michael, an inmate at London Correctional Institution (LoCI) points out, disenfranchisement operates to alienate potentially informed voters. “For those of us behind these walls for an extended period, the perspective of our previous world has been drastically changed. Nowhere is this truer than in politics. Whether out of necessity or boredom, we’ve acquired an awareness that we never previously had. Rather than socializing at the bar, cramming for exams, or scouring the web for the latest viral video, we’ve been debating current political issues, intently watching the news, and poring over countless law books. The irony is we have no say.” Enfranchisement would be advantageous not only to inmates, but to society at large. Inmates have firsthand knowledge of the justice and penal systems that most of us do not have access to, and their particular situations provide a new and important perspective on many issues. As Michael says, “Many inmates have become fully conscious of the issues plaguing our nation and our world. We’ve become informed activists, unlike many of our peers in society. Yet we have absolutely zero influence on our local, state, and federal politics while behind bars and little upon release.” Imprisonment forces many inmates to confront the system in new and critical ways. For some, this leads to an evolved worldview and a deeper understanding of their personal convictions. Take Michael, for instance: "I’ve always been a staunch liberal. I’m not suggesting that my status as an incarcerated individual has changed my position. It is simply now I understand why I believe what I do. Although I came to prison at only 19, I never considered the value of taking a stance on an issue. I would drive by picketers and honk for their tree-hugging cause. When my predominantly black high-school football team was denied service at a local McDonald’s, I donned a jersey with the numbers painted black during the next game. I supported a classmate who was transitioning to a female. However, I never really comprehended the significance of these actions. When I was arrested, I was removed from my element and put in an environment saturated with all sorts of men from different socioeconomic classes, cultural and religious backgrounds, and political viewpoints. It forced me to analyze my positions, not only to substantiate my arguments, but to develop tolerance for those who don’t think as I do." Disenfranchisement also sets a dangerous precedent of reinterpretation by the state, effectively limiting the rights of all citizens under the guise of justice. The distinction between actual rights and merely designated conveniences is a fine line, one that has an immense amount of destructive power. To those of us who have never faced incarceration or the jaws of the U.S. legal system, it may seem justified in its own right to strip those who have committed a punishable offense of their freedoms for a period of time as a form of retribution. However, the extensive abuse of power to which inmates are subjected and their lack of means to defend their rights and humanity reflects a far more sinister and cruel system of discipline. This country is founded on a principle of rights and freedoms that encourages a bottom-up approach to governing. Unfortunately this principle only applies when the state arbitrarily deems someone eligible to vote. The right to vote is only limited by an age restriction and status of citizenship, regardless of access to information or interest in policy. Just because a person has rights does not mean they are forced to exercise them at all times. However, someone who has a vested interest should not be denied the opportunity to contribute as long as said thought or action remains consistent with rights bestowed upon them. Yet, as Mike, another inmate at LoCI notes, “We inmates are denied legitimate means of pursuing self-interest.” This prohibition extends far beyond the ballot. Not only are inmates denied the ability to shape institutional policy through the electoral process, they’re effectively denied the capability to exercise the rights they’re guaranteed under current institutional policy. Aware of their perceived lack of credibility, many inmates remain silent in the face of injustice. Kristie Dotson, the brilliant Black feminist and epistemologist, calls this coerced silencing testimonial smothering. It occurs, she says, when a speaker believes his audience is unwilling to accept his testimony (244). Mike provides an example of this silencing in action: Let’s say you go to prison. You have a complaint, so you go to the unit staff’s office. They’re sitting at the desk chit-chatting with each other when they say, “Come back later. I’m busy.” You try to explain your urgency, but they say, “Who the fuck do you think you are, inmate? Can’t you see I’m fucking busy?” You have no choice but to leave. You don’t want to get a conduct report, because it’s nearly guaranteed that you will be found guilty. This could ruin your chance of being paroled. If it’s your word against an officer’s, even one known to have a history of lying and writing frivolous tickets, they will never side with an inmate against another staff member for fear of being fired. Aware of these structural impediments that effectively silence them, many inmates seek other means to solve problems. Mike continues: Say you’re having a problem with another inmate, so you go in the bathroom and punch him in the back of the head while he’s brushing his teeth. You win admiration and get invited to join a gang, giving you access to friends, money, and drugs. You’re safer thanks to your new affiliation. Later, opiates are found in your cell. You know if you get a conduct report, you’ll be found guilty without a fair hearing. So your gang approaches your cellmate and coerces him into taking the rap. He knows you’ll kick the shit out of him if he doesn’t do it. Even if he doesn’t fight back, he’ll be punished for fighting, he’ll still get beat up, and, because nobody admitted to it, he’ll still get a ticket for drugs. So he takes the rap, and you get away with it. That’s his punishment for being a model inmate, while you’re rewarded for being a thug. The silencing of inmates may actually encourage criminality, the very thing the penal system is meant to purge. As Mike put it: Anybody trying to stay out of trouble and become a better person has the system stacked against him. Anybody selling drugs and manipulating authorities gains control over his environment, ensuring his own survival. If I try to influence a newly-convicted young man to do the right thing, I can’t compete with gang members for his attention. Why come work with me to improve themselves when this seemingly gets them nowhere? It’s no different on the outside. My felony status means I’m not allowed to vote for a higher minimum wage, but I can rob a gas station or sell heroin. This is disenfranchisement, and it’s making your community dangerous. While disenfranchisement of inmates is certainly constitutional, we must question if it violates inmates’ fundamental human rights and also if it is in the best interest of society at large. The benefits to enfranchising the inmate population, both by allowing them the right to vote and by taking their testimony in all matters seriously, are two-fold. It would fill epistemic gaps by allowing the particular knowledge of inmates into public discourse, and it could potentially reduce criminality, which is the very goal of the penal system. We leave you with a plea from our friends on the inside: “For the greater good of our nation, we on the inside implore those of you capable to champion for change to contact lawmakers and insist they add this population of informed voters to their constituency.”

Works Citedand Images Dotson, Kristie. "Tracking Epistemic Violence, Tracking Practices of Silencing." Hypatia, vol. 26, no. 2, May 2011, pp. 236-257. Academic Search Complete. Web. US Const. amend. XIII, sec. 1. US Const. amend. XV, sec. 1. Image 1: http://launch.durangoherald.com/articles/108912-most-jail-inmates-have-the-right-to-vote-but-few-do Image 2: http://drexel.edu/now/archive/2016/January/Prison-Project/ Image 3: http://www.vipublicdefender.com/know-your-rights Image 4: https://race-and-social-justice-review.law.miami.edu/felony-disenfranchisement-presidential-election/

2 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm a philosopher, a writer, a thinker, an Inside-Out Prison Exchange Instructor. I do a lot of these on the road as part of recognizing the value of philosophy as a public practice. Archives

October 2018

Categories |

Wittenberg

|

Buy Now |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed