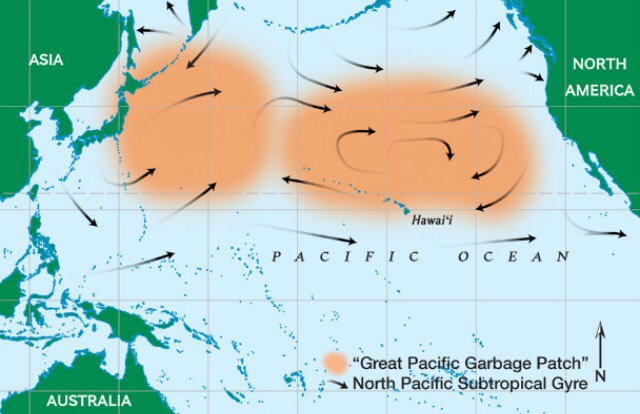

The out of sight, out of mind philosophy, unfortunately, can be applied to the care of our Earth. Often seen as a simple and cheap solution to various problems, including waste disposal, this method our world has adopted has led to potentially one of the most dangerous phenomena on our planet. 54% of the waste produced in America is “disposed in some type of landfill.” What would typically come to mind is an image of a “dump,” in which garbage is deposited into a man made hole in the ground, but landfills can come in another form: our oceans. The threat of groundwater contamination from landfills has always been an issue at hand, so imagine what devastation and impact that could mean for the countless life forms found in the ocean (Clowney and Mosto 363). The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a collection of marine debris in the North Pacific Ocean. It is considered the world’s largest landfill, and it floats in the ocean. The garbage patch spans the water from the west coast of the United States to Japan. Two separate patches have formed, the western—near Japan—and the eastern—located between Hawaii and California. The area is a slow-moving, clockwise spiral of currents created by a high-pressure system of air currents. By nature of the gyre, they accumulate plastic, other trash and natural parts of the ocean such as seaweed (National Geographic). Scientists consider the specific area as an oceanic desert. It is filled with tiny phytoplankton but contains very few big fish or mammals. Due to this fact fisherman and sailors rarely travel through the area. It is estimated that millions of pounds of trash, mostly plastic reside the waters. It is anticipated that plastic comprises about 90 percent of the trash in marine waters. In 2006 the United Nations Environment Program reported an estimate that claims that in every square mile of ocean 46,000 pieces of floating plastic is present. In some areas the amount of plankton is outweighed by trash by a ratio of 6:1. In a given year the world produces more than 200 billion pounds of plastic, scientists believe 10 percent ends up in the ocean (5 gyres). 70 percent of the plastic sinks to the bottom of the ocean resulting to in damage to life on the ocean floor. The remaining floats. The main problem with plastic is it does not biodegrade. The durability that makes it useful to humans causes the harmful effects to nature. Plastic over time will break into smaller pieces of plastic without breaking into smaller compounds. A single plastic microbead can be 1 million times more toxic than the water surrounding it (National Geographic). The smaller parts of plastic ultimately get ingested by filter feeders or other marine animals and result in serious damage to their bodies. The effects are cascaded and cause threats to entire food chains. Filter feeders and smaller marine animals will get eaten and the poisonous effects of the plastic within their bodies are passed onto the predator. The garbage patch presents several threats to fishing, marine life and tourism. The LA times estimates that 80 percent of ocean trash originates from the land (5 gyres). Scientists that study the effects of trash in the ocean nearly all conclude that searching and eliminating the ocean of its trash is impossible. Experts believe the solution to managing the trash within the ocean can be traced back to trash management on land. We must tackle the problem at its source (National Geographic). The world’s waste is disportationally placed. Peter Wenz discusses environmental racism, which is the disproportional distribution of the burdens of waste unto the weakest and poorest of a nation and ultimately the world. The population makeup of the weakest and poorest populations tend to be nonwhite minorities. Throughout his essay “Just Garbage” he brings up several points that show how unevenly the burdens of waste are being distributed, and how current practices are only worsening the situation with an “out of sight out of mind”/ “as long as it’s not in my backyard” mentality. Wenz examines our consumer-oriented society, which puts high value on throwing away the old and replacing it with the new. Humans within industrialized countries focus on the newest and most improved products, hence their old products are thrown out to make room. Despite his anthropocentric view within his essay, his theory can be connected to all species. As with The Great Pacific Garbage Patch it is evident that the poorest and weakest species is being left with the burden of human waste. The native sea life is being drastically affected by humans’ “progress” and material lifestyles. All the waste that is disregarded to allow new materials ends up somewhere, and with many people fighting to keep it away from themselves, it sometimes ends where there are no voices to be directly heard. Wenz is a strong believer in those who reap the benefits of waste should equally share in the burdens of waste, instead of one group (a certain race or species) gaining all the benefits while another struggles to keep up with the burdens. Just like the minorities of a human society, the inhabitants of the ecological society are currently suffocating under the tax of waste. Wenz proposes a solution, LULU, which is a plan to evenly distribute the burdens of waste. With this plan different communities would be examined and each community would then be give the amount of waste it can handle. If Wenz’s LULU plan is followed all types of minorities would benefit. By switching from one group taking on all of the burdens, to all groups equally sharing the distribution of waste minorities will have greater opportunities to prosper. The plan Wenz puts forward to help humans can be generalized to the environment as a whole. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch doesn’t have to exist, and its inhabitants don’t have to struggle under the weight of waste alone (Clowney and Mosto, 368-376).

Bluntly, we have to clean this up. We must adapt our actions and mentality on our own waste. The problem however, is that the patch is located so far away from any national coastlines that no countries want to claim responsibility for it. Charles Moore, the discoverer of the patch, has stated that the cleanup process would bankrupt any country that attempts it. However, there are many international organizations and individuals who are actively pushing for awareness of it (The Ocean Cleanup). Also, to simply just pick up the amount of trash that is currently in the Patch would take, according to the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration’s Marine Debris Program, 67 ships a total of one year to clean up less than ONE percent of the North Pacific Ocean. Fortunately, there is a better and more efficient solution than going out with boats and picking up the trash out of the ocean or using nets that can capture other sea life. The Ocean Cleanup company is planning on using the oceans own currents to solve the problem. They plan on setting up a 100km-long v-shaped barrier that the ocean currents will pass through. This will form a screen that will collect the plastic. The screen will be short enough in design to allow for neutrally buoyant marine life to drift through, lowering the impact the cleanup would have on ocean life. The Ocean Cleanup’s feasibility study indicates that one 100 km long barrier “could remove 42% of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch over a period of 10 years” and they also claim that their most conservative measurements amount to 70 million kilos of plastic at 4.53 Euros per kilo. This is expensive but a lot quicker and cheaper alternative. It has passed model tests, and a 4 m long model that confirmed computer models. A coastal 2000m long model will be put to the test off the coast of Japan this year. If all works out for them they could be able to put the full scale model in the pacific in 2020. Recycling. We currently only recover 5-10% of the plastics we produce worldwide.The environment lacks the ability to speak for itself. The result of our human waste has presented environmental dangers. The development and growth of the Great Pacific garbage patch presents an extremely difficult challenge. Our current generations have increased awareness of preserving the environment and protecting it for future generations.The increase of recycling, biodegradable product demand, and other steps we have implemented to reduce waste has made it possible to slow the growth and has even begun to reduce the size of the world’s largest dumping ground. In a broader and more preventative sense, the problem we currently face with waste disposal can be tackled with waste management. Many believe if we continue returning to the good old-fashioned 3 Rs: reduce, reuse, recycle, a large impact can be made. One of these approaches is described as industrial ecology, which turns the relationship between industry and manufacturing into its own ecosystem. In other words, the “waste products of one industry become the raw materials of another.” (Clowney and Mosto, 365). Scientists agree: if the oceans die, we die. The underlying problem with environmental pollution is the constant increase industrialized countries produce annually. We must change our economic practices and cognitions in order to preserve the environment. We can fix the world’s largest unintentional dumping ground. Citations: Clowney D., and Mosto P. Earthcare: An Anthology in Environmental Ethics. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield; 2009. Print. 363- The Ocean Cleanup. Technology. Website. 2015. National Geographic. Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Website. 2016. 5 Gyres. The Plastic Problem. Website. 2016. Image credits: http://www.appliedtechnotopia.com/post/51385460758/this-infographic-really-puts-the-great-pacific (Picture with man in canoe) https://wavepatrol.wordpress.com/2010/10/08/the-plastic-shore-waste-build-up-in-the-north-pacific-ocean-twice-the-size-of-texas/ (Picture underwater) http://www.buzzfeed.com/chernobyldiaries/places-you-never-want-to-go-on-a-vacation?sub=1550838_275379 (Map picture) https://usresponserestoration.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/pacific-garbage-patch-map_2010_noaamdp.jpg

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI'm a philosopher, a writer, a thinker, an Inside-Out Prison Exchange Instructor. I do a lot of these on the road as part of recognizing the value of philosophy as a public practice. Archives

October 2018

Categories |

Wittenberg

|

Buy Now |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed